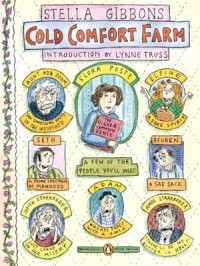

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons

Have you ever read one of those novels full of doom and gloom, peopled with characters trapped by their own twisted, thwarted passions, and thought that with some energy and common sense their problems could be easily resolved? That is what Cold Comfort Farm is supposed to be about – taking a farmful of such isolated, romantically tormented folk and letting Flora, the brisk, no-nonsense young cousin from the city, sort them out. It is supposed to be a hilarious parody; unfortunately, apart from a few mildly humorous moments it did not tickle my funny bone. Perhaps the problem is that I haven’t read enough of the novels it mocks: Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence, Mary Webb. Though I’ve read Wuthering Heights and a couple Hardys, my poster child for the type of novel described above is One Hundred Years of Solitude, written decades after this one.

At any rate, this is a strange novel, as parodies usually are. Though published in 1932, it is set in “the near future” – apparently the 1950s, though it looks a lot like the 1930s, with more advanced communication and transportation, and with no WW2 in its past. It takes aim at farm life, at overly emotional and melodramatic folk (people at Cold Comfort are forever throwing themselves down wells out of despair over something or other), but also at city folk, particularly if smug and pretentious. There’s a male novelist who sees sexual imagery in everything and is convinced that Flora won’t kiss him because she’s inhibited (actually it’s because he’s unattractive), and when Flora is in London she considers taking her cousin to see an avant-garde play, described as “a Neo-Expressionist attempt to give dramatic form to the mental reactions of a man employed as a waiter in a restaurant who dreams that he is the double of another man who is employed as a steward on a liner, and who, on awakening and realizing that he is still a waiter employed in a restaurant and not a steward employed on a liner, goes mad and shoots his reflection in a mirror and dies. It had seventeen scenes and only one character.”

There is also quite a bit of lampooning of purple prose, in the form of describing everything in a ridiculously overheated manner (the “best” passages, meaning the most purple, are marked with asterisks). For instance:

“Amos looked at her, as though seeing her for the first, or perhaps the second, time. His huge body, rude as a wind-tortured thorn, was printed darkly against the thin mild flame of the declining winter sun that throbbed like a sallow lemon on the westering lip of Mockuncle Hill, and sent its pale, sharp rays into the kitchen through the open door. The brittle air, on which the fans of the trees were etched like ageing skeletons, seemed thronged by the bright, invisible ghosts of a million dead summers. The cold beat in glassy waves against the eyelids of anybody who happened to be out in it. High up, a few chalky clouds doubtfully wavered in the pale sky that curved over against the rim of the Downs like a vast inverted pot-de-chambre. Huddled in the hollow like an exhausted brute, the frosted roofs of Howling, crisp and purple as broccoli leaves, were like beasts about to spring.”

If you are laughing by now, you should read this book.

At any rate, I suspect my reaction has something to do with the book’s age; what might have seemed sensible and a happy ending in 1932 don’t seem like such a good idea in 2014. For instance, Flora’s “solution” for her 17-year-old cousin, Elfine, is to get her hastily married off to a pleasant but slow-witted son of the local gentry, by dint of giving her a makeover, talking her out of her favorite pasttimes (long walks in the Downs and writing poetry), and cautioning her not to appear too “brainy.” As a recipe for long-term happiness, what could possibly go wrong?

But ultimately, this is a novel that’s just too bizarre – from a cow’s leg randomly falling off and getting lost, unnoticed by the elderly manservant, to the tyrannical great-aunt whose dialogue consists almost entirely of “I saw something nasty in the woodshed!” – for the story to stand alone for those who don’t find it funny. And Flora achieves her goals too easily, once she begins dragging her relatives one at a time out of their ruts, for there to be any real suspense. I'm calling it 2.5 stars, because it is easy and light reading and in that sense not unpleasant, but it isn’t a book I’d personally recommend.

6

6