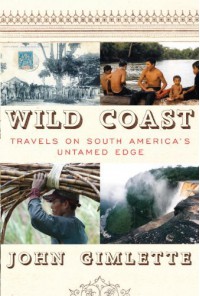

Wild Coast by John Gimlette

I was initially excited about this book, which describes a wild, little-known part of the world in vivid detail. However, that excitement soon wore off, as Gimlette seems largely drawn to describing war and atrocities, to emphasizing atmosphere over accuracy in his reportage, and to following the stories of white explorers and colonists while stereotyping and relegating everybody else to the sidelines, even though “everybody else” makes up 99% of the population.

The book is structured around Gimlette’s travels through “the Guianas,” three relatively small countries carved out of the Caribbean coast of South America, but which have remarkably little in common with the rest of the continent. Or rather, two countries – English-speaking Guyana and Dutch-speaking Suriname – plus French Guiana (referred to here as “Guyane”), an overseas department of France. These countries’ populations are mostly descended from the black slaves and Indian indentured servants brought there to work the sugar plantations; there’s also a small native population and, in Suriname, villages of “maroons,” descendants of escaped slaves who, centuries ago, formed their own tribes in the jungle. A little over half the book focuses on Guyana and most of the rest on Suriname, with just one 40-page chapter covering French Guiana.

It’s definitely interesting material, and Gimlette devotes perhaps half or less of the book to his travels, while the rest relates the bloody history of the Guianas. I definitely learned a lot from it: Gimlette clearly did a bunch of research, and he visits many sites of historical import and relates stories revealing the significance of these places to the reader. When covering more recent history, he talks to people who experienced historical events, sometimes including key players as well as everyday folk. He travels widely around the countries, from the coast, where 90% of the population lives, to the jungle and the savannah, and meets people from all walks of life. He has an eye for the bizarre, describes his surroundings in colorful detail, and has a smooth, assured writing style.

That said, the more I read of this book, the more disenchanted I became. Gimlette seems drawn to the horrifying, whether it’s the barbarity of slavery or French Guiana’s penal colony, the horrors of recent civil wars, or the mass suicide/massacre of an American cult at Jonestown; this is not a light or easy read, though its tone is often flippant. Gimlette’s writing is atmospheric, but not well-sourced: despite the fact that the book is largely history, it has no endnotes, only a description of his sources generally. And he seems to play fast and loose with the facts. “Even as I write, there isn’t a single road that leads from the Guianas into the world beyond,” he tells us at the beginning, before taking a bus through French Guiana to the Brazilian border at the end. In writing about the Jonestown cult, he asserts that “Jonestown carried on killing for years after the massacre. . . . Even years after the cult’s demise, defectors were still being hunted down and killed” – a claim the internet does not seem to support.

But it’s not uncommon for him to leave his facts vague (who is supposed to have killed the defectors, given that Jones’s loyal followers had already killed themselves?). When discussing Sir Walter Raleigh’s final, ill-fated expedition into the rainforest, he describes in detail the suicide of Raleigh’s friend Captain Keymis and Raleigh’s own execution back home in England, but fails to note why Keymis killed himself or why Raleigh (who comes up time and again in this book) was executed, beyond the vague statement that “the expedition disintegrated into a bloody brawl.” I had to turn to the internet to learn that, in fact, Keymis lead an expedition against the Spanish without Raleigh’s permission, in which Raleigh’s son was killed; Keymis killed himself because Raleigh refused to forgive him, and Raleigh was executed because the skirmish violated the terms of his own parole on a questionable prior conviction for plotting against the king. It’s as if Gimlette wanted to include their deaths for the extra color and weight they lent the story, but couldn’t be bothered to share the facts from which a reader could make sense of them.

And then there’s the fact that so much of the book is focused on white European men like Gimlette himself, even if they did nothing more than wander into the jungle and die (see Raymond Maufrais). It winds up giving the impression that only these people’s stories are worth telling, particularly alongside Gimlette’s ready stereotypes of everyone else. The Amerindians, apparently, are cannibals, as are the Africans. Escaped slaves who set up fiefdoms full of brutality and debauchery are “reverting back to old Africa,” despite the fact that this is how the colonists operated toward them.

So ultimately, I can give this book a cautious recommendation at best. It’s a colorful introduction to a world about which little has been written, but it’s also a heavy read, imbued with the author’s biases and questionable, unsourced assertions. Too bad, for a book that began with such promise.