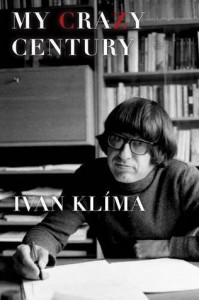

My Crazy Century by Ivan Klima

There are two kinds of memoirs. The first is literary memoirs, which you read because the story they tell is interesting or because they’re renowned as good books. You usually don’t know anything about the author beforehand, and don’t need to. The other kind is celebrity memoirs, which you read because you are already interested in the author. Because these books have a built-in audience rather than having to contend for readership with all other books on a literary footing, and because their appeal has more to do with learning facts about a celebrity than getting a great story, their quality often suffers.

This book reads like a celebrity memoir, with the added disadvantage that I’d never heard of Ivan Klima before picking it up. Klima is a Czech writer who has had some interesting life experiences: he and his family were in an internment camp during World War II due to their Jewish heritage, and he went on to become first a Communist party member and later a banned writer under the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, a country he refused to abandon despite petty harassment from the government. But the concentration camp portion only takes up 15 pages of this 534-page book, which turned out to be a dryly-written tome. Klima spends a lot of pages talking about his career: name-dropping writers he edited or was friends with, providing long plot summaries of stories and plays he wrote, and describing trips he took abroad and conferences he attended and who said what in their speeches. This is the part that felt most like a celebrity memoir, because it would be interesting mostly to dedicated fans of Klima who have a Who’s Who of 20th century Czech writers in their heads. If you don't, there's nothing in Klima's descriptions of them to distinguish his friends from one another.

Klima’s other major topic is the political climate at the time, but in a narrow sense: he was intensely interested in those regulations affecting writers and art, as well as the speeches and articles exchanged between the regime and its critics. He quotes portions of proclamations, opinion pieces, and speeches at length, including his own. But it would be hard to put together a picture of the times from this book, and given that he originally wrote it for a Czech audience, I’m not sure that was his intent. When the Velvet Revolution overthrowing Communism happens within the last few pages, he doesn’t name it and it was unclear to me exactly what was happening and why. Try Street Without a Name for a far more vivid picture of life under Communism in Eastern Europe.

Meanwhile, while some of the details of life at the time are interesting, the book contains little in the way of feelings, insight into those around him, and reflections on the author’s personal life beyond the bare facts. He mentions cheating on his wife, without any reflection on what other than the other woman’s attractiveness caused him to do so, and informs the reader that he and his wife then confessed affairs to each other, at which point, “We put aside our infidelities, at least from our conversations” – and that’s all he has to say about the subject. Later there’s another affair, equally opaque to the reader, after which he again confesses and concludes with “But I do not intend to compose a chronicle of my love life and my infidelities. My wish is not to draw my loved ones into my tale; it’s enough that I drew them into real life.” It’s a bare memoir that doesn’t draw in the writer’s loved ones, like it or not. But beyond that, if he doesn’t want to write about the subject, why bring it up at all? So I’m back to the celebrity memoir explanation: he appears to feel a need to include the facts of situations in his life, even without corresponding examination of feelings or relationships. But, not being an Ivan Klima fan, I don’t care about the bare facts. I was looking for a story, and didn’t find it.

Then there are the essays. The book ends with 118 pages comprising 18 pieces on various geopolitical topics. These read like the opinion papers of an undergraduate political science student, speaking in broad generalities and without fresh insight. For instance, he writes an entire essay on the fact that youth are more susceptible to extremism because they are less invested in the existing system and more naïve, idealistic and excitable than older adults. (Genius!) He leans heavily on broad generalities about extremism, attempting to apply his experience with Nazism and Communism to modern-day terrorism at every opportunity. This creates the impression that he believes he needs to offer insight into terrorism to keep his book “relevant” for modern readers. But he’s never encountered terrorism and has no insights that any other commentator couldn’t offer.

Overall, I found this work dry, impersonal, unnecessarily long, and a slog to read, despite its promising subject matter. Somehow, although it’s roughly twice the length of the average American memoir, it is abridged from the two-volume Czech version; I can only assume that Klima’s fans are dedicated, at least in his home country, and be thankful that the English-language publisher chose to abridge it.