Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

This is by far Jane Austen’s most popular book, and while as a kid I found it dull and slow, re-reading as an adult I had a great time with it. It’s easy to see where that popularity comes from. First, unlike some of Austen’s other books, which just have some romance in them, this one actually is a romance, in that it’s structured around the growth of and obstacles to Elizabeth’s and Jane’s relationships.

Second, to the extent that it moralizes (and Austen always moralizes to some extent), it’s mostly about issues that remain both relevant and palatable today: the dangers of assuming yourself better than everyone around you, of clinging to a negative first impression despite new information, of taking people at their word when they eagerly insist to virtual strangers that all their problems are other people’s fault.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Elizabeth is a great heroine. She’s witty, energetic, and has a sense of humor, which makes her fun. She’s intelligent, caring, and has a backbone, which makes her admirable. And she’s judgmental, jumps to conclusions, and has some learning to do, which makes her human.

Warning: there will be SPOILERS below.

There isn’t much I can say about this book that hasn’t already been said: it’s well-written, engaging, and to an adult reader, it’s quite funny. It’s the perfect piece of intelligent escapism. It’s full of well-drawn and realistic characters, many of them a little bit ridiculous, and the author invites us to laugh at them with her. It isn’t “just” a romance, but explores the intersection of love and money in Austen’s society—though for all that, Austen’s heroines aren’t as mercenary as some make them out to be. At the end I think Darcy is genuinely in love with Elizabeth, while she’s still in the early stages of infatuation, overwhelmed by the fact that this rich and handsome man cares enough to put himself out on her behalf. But I don’t think it’s just about the money either.

I do wish Austen didn’t lapse into narrative summary at the most inconvenient moments, like proposal scenes (!). I actually didn’t remember that Georgiana appears in person in this book, probably because although she and Elizabeth meet several times, none of Georgiana’s lines are ever transcribed for the reader. But Austen was in many ways pioneering the modern English-language novel, so it’s inevitable that not everything was perfect, and impressive that despite that she was able to write characters who still manage to inspire emotional investment today.

I’ll use the rest of this space to comment on some characters I viewed differently this time around. First, the treatment of Mrs. Bennet is rather sad: it’s true that her perspective is limited, but she actually is trying to do right by her daughters, and she obviously loves her husband more than he loves her. Given that the Bennets are on good terms with what seems like a large circle of acquaintance (her claim that they dine with 20 other families is meant to be ridiculous, but is impressive by today’s isolated standards), I suspect her manners are quite good enough by her neighbors’ standards, and it’s the stuck-up Bingley sisters and Mr. Darcy who judge her. It’s a little sad that their happy ending requires Elizabeth and even the otherwise-angelic Jane to distance themselves from her.

Lydia, on the other hand, would be a strong candidate for the heroine if this were a modern novel. Modern audiences seem to love the young woman driven by sexual or romantic passion to flout societal convention just as much as Austen’s society hated her. Particularly sympathetic in Lydia’s case is that she actually loves Wickham but is deceived about his regard for her. Lydia’s exuberance also makes her fun to read about, though because she’s a teenager and not the heroine, she has all-too-human flaws as well: she’s self-absorbed and can’t be bothered to listen to anyone she disagrees with. The scene where she claims she’s “treating” Jane and Elizabeth to lunch, but makes them pay because she already spent her money, is particularly amusing.

Then there’s Mary. Before I thought of her as a typical teenager in her high regard for her own intellect, and starting out here I was sympathetic to her based on her position alone. She’s the only unattractive one out of five sisters (ouch), and also the only member of the family who doesn’t seem particularly beloved by anyone else: her older and younger sisters are each a close-knit pair who also have good friends outside the family, while the parents each have their favorites, all of it excluding Mary. On this reading, though, it seemed likely that Mary is on the autism spectrum, though to Austen’s and therefore Elizabeth’s eyes it just looked like cluelessness. Mary is sententious and blind to social norms, and unlike with Lydia, it isn’t because Mary doesn’t care (she’s visibly embarrassed when her father calls her out at a party). The scene that clinched it for me comes after Lydia’s disgrace, when Mary approaches Elizabeth to suggest that they should “pour into the wounded bosoms of each other the balm of sisterly consolation,” which Elizabeth considers so bizarre that she makes no response. This seems to indicate that either Mary actually does not realize that she and Elizabeth don’t have this kind of relationship, or she’s trying to bond with her but has no idea how to do so. Unfortunately, Mary seems unlikely to improve in understanding when no one can be bothered to explain anything to her.

Reading this right after Emma, I was surprised by how different it felt: shorter chapters, more dialogue, and rather less polished, but perhaps more fun. It didn’t touch me particularly deeply, but I did enjoy it a lot and it also gave me plenty to think about. That’s what makes it a true classic I suppose, that there’s always more to discover and new perspectives to see upon re-reading.

2

2

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

In my adult re-reading of Austen’s major works, I came to this one after having a lot of fun with Emma and Pride and Prejudice, and therefore with high expectations. It disappointed a bit, in part for reasons not embedded in the text at all—character portrayals from the 1995 movie kept intruding—in part because as it turns out, even with a master you can tell when you’re reading a debut novel, and in part due to certain elements that have not aged well.

Warning: there will be SPOILERS below.

Austen’s novels have a reputation for being romances, but interestingly, other than Pride and Prejudice and perhaps Persuasion, they aren’t at all, not in the sense of the plot being focused on and structured around a love story. Somehow this label seems to get stuck indiscriminately on classics by women that have weddings at the end; when Shakespeare did it we called them “comedies” instead. So I was surprised by how little we see, in this book, of Elinor and Marianne’s relationships with the men they wind up marrying: Elinor and Edward have fallen in love off-page before the book begins, and see each other rarely during its pages, while from an adult viewpoint it’s hard to argue that Marianne falls in love with Colonel Brandon at all. She seems rather to bow to the inevitable, having been through a devastating heartbreak once and with all her family pushing the match; creepily, Elinor refers twice to wanting her own sister to go to Colonel Brandon as a “reward” for his good behavior.

Instead, this book is a parable about the advantages of sense over “sensibility” (emotion and romance), with Elinor embodying the former and Marianne the latter. The narrator is always poking us to point out how Elinor manages to get what she wants while being polite, while Marianne only causes trouble by being impulsive and oblivious. The problem is that Elinor, our heroine, is tiresomely perfect and a wet blanket. In the abstract, I identify with many of Elinor’s traits, but in concrete terms I didn’t find much to like or relate to in this particular character: she’s just sort of carried along by the plot, without seeming to yearn for anything (except perhaps that guy she fell in love with beforehand, but then she’s not exactly doing anything to pursue the match). She’s no fun; she’s almost just an avatar of what a sensible young woman at the time was supposed to be. It’s telling as to the differences between our modern culture and Austen’s that in the book, it’s Marianne who needs to change; in the film, it’s Elinor.

Though the ending does seem to muddle this a bit. Elinor’s ending is a happy one only if we assume a deep and lasting romantic connection: otherwise she’s just stuck living in a cottage on a third of the income she previously told us she wanted, as a tenant of the wealthy man who becomes her younger sister’s husband. Marianne, meanwhile, winds up with the material advantages, including exactly the income she wanted. One wonders how each feels about her situation ten, twenty, thirty years in the future. It’s not nearly as clear-cut a happy ending as I remember from childhood, when all I noticed was the weddings and the fact that the sisters are still together.

The most disturbing part of the story, though, is the treatment of the two Elizas, characters we never meet but who nevertheless figure prominently. The elder Eliza is the great love of Brandon’s young life, which doesn’t stop him, when he comes back from fighting abroad and finds her in jail for debt with her illegitimate toddler, from considering the fact that she’s also dying to be a “consolation.” This is made more horrific by the fact that Brandon is the single most important person in Eliza’s life from childhood: she’s an orphan, he was her best friend and protector. Although Austen treats his reaction with approval, there’s something profoundly inhuman about this notion that she can never be redeemed even in the eyes of the person who has always loved her most, that the best she can do is cease to exist.

Because of that I can’t help wondering if a real man of that time period in Brandon’s position would actually have thought this way, or if this is simply Austen—who was presumably never in this position herself—projecting what others who have also never been in this position believed he should have felt. Or, hell, maybe Brandon himself didn’t actually feel that way, but is moralizing in retrospect about his own story because it’s the only way he can live with it. But at any rate, Elinor approves, which is hardly to her credit. She also approves Brandon’s subsequent decisions, which involve farming out the young orphan, the younger Eliza, to be raised by someone else, then being shocked when as a teenager and most likely feeling unloved and unwanted, she jumps into an ill-advised romance, and then banishing her to the countryside alone with her baby. One hopes that she manages to raise her own child with a more solid and loving foundation than the last two generations have had.

So it’s kind of hard to wrench my attention back from that situation to the social lives of Elinor and Marianne, though it does seem like Austen tempered the horrible fates of her “fallen women” in future books: Wickham, who seems like a later version of Willoughby, is just as much a seducer, but Georgiana escapes in time with no loss of reputation or her brother’s love, and Lydia is redeemed through marriage in the eyes of all but the most judgmental (who never liked her much anyway). In that sense, it’s strange that Wickham is perhaps drawn as more of a scoundrel than Willoughby, who regrets what he’s done to Marianne (though not Eliza), in a drunken confession that feels unusual for Austen and almost like wish-fulfillment. But Elinor pulls it back into the realm of the realistic with the astute observation that it’s easy for Willoughby to regret the consequences of decisions he’s already made; that doesn’t mean he’d actually have been happy with the alternative.

This book doesn’t flow quite as smoothly as some of Austen’s later works, but it is still engaging and a lot of the secondary characters are just plain fun to read about: John and his money-focused blindness, Mrs. Jennings with her bad manners but good heart. I did enjoy reading it, though not as much as some of her other work, which was written with a bit more experience and has aged better. Though frankly, anything over 200 years old that is at all enjoyable or says anything to anyone today has aged far better than most, and considering the state of the novel at the time Austen wrote this one, it’s quite an achievement.

2

2

Emma by Jane Austen

I have a rocky relationship with Jane Austen. I first read her major works for bragging rights when too young to appreciate them. Then as an adult, I read Mansfield Park and Persuasion, and decided, nope, Austen wasn’t for me. And then I read Northanger Abbey. And it was fun! And funny! So recently, I embarked on a re-read project of Austen’s three most popular works, and what a difference those intervening years have made.

Warning: there will be SPOILERS below.

First of all, I have a strong preference when it comes to Austen’s novels: I enjoy her wit and insight, but not her moralizing, which is why I had great fun with Emma, Pride and Prejudice, and Northanger Abbey, but found her other books to drag. Her dynamic, imperfect heroines, the ones with real foibles to poke fun at, whose journeys involve needing to grow and change as they learn more about the world and themselves: these are great fun to read about. Her static, flawless heroines who don’t go on a journey so much as stand by while others learn to better appreciate their perfection: ugh, no thank you.

Happily, Emma falls into the first category. It’s one of Austen’s longer books, and I remember taking forever to read it, but this time I burned through, finding the story compelling and fun. It feels a bit more polished than some of Austen’s work, with longer chapters that flow naturally together. It’s also a little ridiculous with its endless misunderstandings, but each one individually is believable. Its characters feel real, and Austen’s observation of certain aspects of human nature is dead-on: Mr. Woodhouse, who allows his high levels of anxiety to control his life and limit the activities of everyone around him, is so much like some real people I know that I was irritated at him every time he appeared on the page. For all her flaws, I can’t help thinking Emma’s a bit of a saint for so patiently putting up with him.

Most interestingly though, as it turns out few people (including my younger self) seem to realize what this novel is actually about. It’s not a romance: for most of the book Mr. Knightley acts the part of a father-figure to Emma, she doesn’t realize her feelings for him till near the end, and before that point there’s only one brief moment of chemistry between them; romance is her reward at the end, but not the subject of her story. It’s not about a young woman facing financial or familial pressure to marry: unique among Austen’s heroines, Emma has no actual need to do so, and no one voices any objections to her stated plan to remain single and eventually adopt one of her nieces for company. It’s also not about Emma’s learning not to try to set up her friends: she actually learns that lesson pretty early on.

In fact, this is a very conservative novel about a young woman learning her proper place in society and how to behave as befits her station as the highest-ranking woman in her rural town. Emma has to learn to be charitable and patient toward the genteel but unfortunate (Miss Bates), not to snub the nouveau riche as long as they remember their place and treat her with proper respect (the Gardners), and to choose as her friends the worthy and well-bred (Jane Fairfax) over people of lesser birth, with whom too close a friendship will inevitably cause trouble and social disorder (Harriet Smith). It’s hard to say much for this sort of message now. For modern audiences, the less charitable parts of it—the message that Emma must ultimately drop Harriet as a friend to maintain proper social order, hammered home through the way Emma’s machinations to keep Harriet within her circle cause escalating trouble until finally Emma herself is done with the friendship—are so obviously unfortunate that people tend to read the novel as being about something else entirely. Austen makes it easy to do that, with several subplots and layers to the story. But I doubt her contemporaries would have missed that the entire novel is about a young woman’s journey toward “correct” behavior, dressed up in a bunch of drama and poking fun at people in a small town society.

All that said, it’s an enjoyable story in its own right, and makes for such lovely escapism while giving the reader multifaceted characters and issues with some real depth to chew on, that I can’t give it less than 4 stars despite rather unfortunate themes. Maybe one day I’ll return to it again and see something completely new.

2

2

Laura Bassi and Science in 18th Century Europe by Monique Frize

This is a lazily researched, poorly-organized and poorly-written book, that nevertheless proved interesting to me by covering the biographies of 18th century female Italian scientists, which I have not found elsewhere. Biographies available in English are overwhelmingly Anglocentric and a historical biography of a non-English speaking woman without an adventurous sex life is a rare find indeed.

But unless you have a strong interest in that subject, you probably shouldn’t read this book. First of all, it’s poorly researched. The author apparently cribbed most of it from the dissertation of a researcher who died prematurely, and that researcher appears to have done much more work on it than this author, who regularly cites to Wikipedia (!). Second, she seems to run out of material about halfway through after already having covered Laura Bassi’s biography and some background on science at the time, so spends the rest of the book summarizing letters Bassi exchanged with various men (unclear why this isn’t simply incorporated into the biography portion) and providing mini-biographies of other Italian women active in science.

Third, the writing is just bad; I think the author is a science professor who is interested in the subject but very much not a writer. She struggles with appropriate prepositions, capitalization, and hyphenation, and there’s frequent awkward sentence structure and word use (words like “obtention” and “embracement”). She also frequently reminds readers of things we’ve already been told, going so far as to use Bassi’s full name and remind us of basic facts such as the city in which she lived well into the book, giving the impression that no final read-through was conducted to streamline the writing. Overall, it’s just rather awkward and jagged.

That said, it definitely is an interesting subject: Laura Bassi was a professor of science in 18th century Italy, which was quite an achievement for a woman at the time, and if the book doesn’t exactly bring her to life, it definitely introduces a lot of facts about her. As it turns out, Italy offered somewhat more opportunities for educated women in the 18th century than other European countries, largely based on the notion of the “exceptional woman,” whose brilliance reflected well on her family and city because since women were assumed to be less intelligent than men, if a woman was that smart, how brilliant must their men be? In general, these “exceptional women” were expected to adorn civic occasions rather than make actual careers, and to be very much the exceptions to the rule: the father of one of them, who had championed his own daughter’s advancement, argued successfully against the same university granting a degree to any other woman on the grounds that it would somehow cheapen his daughter’s achievement. Bassi managed to turn her degree into an actual career though, with some help from unexpected places, namely the Pope, an old friend of hers who wanted to improve the state of science in Bologna at the time.

I would love to see someone write biographies of the women discussed here for a general audience; there’s so much rich material that would be new to most English-speaking readers, and the information included here certainly expanded my understanding of history a little. That said, it is very difficult to recommend this particular book.

The Prince Who Would be King by Sarah Fraser

I thought it would be interesting to read about the young life of a crown prince; this is a time of life usually skated through quickly in biographies, but since this particular Prince of Wales (Henry Stuart, 1594-1612) died at age eighteen, the whole book is about his young life.

Unfortunately, the book is quite dry: perhaps proof that historical figures’ childhoods aren’t meant to be given this much attention, or perhaps just due to the author’s writing. Henry didn’t actually get to do very much, and there’s a lot of information about the large number of people around him, most of whom come across as relatively interchangeable in their portrayals, alongside descriptions of court entertainments, etc. When the author dips into the European politics and warfare at the time, though, it’s still presented in a dry manner, though I learned a bit from it.

Fraser is clearly enamored of Henry, which I suspect is common for biographers – especially if they aren’t guaranteed bestsellers, it probably is a labor of love – but it was not an affection that translated itself to this reader. Of course it’s always sad when a teenager dies (here, probably of typhoid fever), but Henry comes across as a militant Protestant eager to go make war on Catholics and colonize anybody he could. Yes, he was a boy, but with the power of monarchy and surrounding himself by people who thought the same, he likely would have carried all this into adulthood.

Also, a quick grammar lesson: when you write things like “Bleeding from the womb, the queen’s ladies crowded round and led her away,” you are saying that all the queen’s ladies are bleeding from the womb, not the queen, who is the one actually miscarrying here. Unfortunate sentence structures like this appear throughout the book.

So, while this is a short book (only 266 pages of text followed by endnotes), it took me awhile to read as I rarely had much desire to pick it up. I did learn some things about the time period and found some of the details interesting, and certainly Fraser seems to have a thorough knowledge of her subject and to have located numerous primary sources. But it was a bit of a drag and I can’t say I got much out of it in the end. Perhaps a group biography of Henry along with some other family members or close associates might have been a better way to go.

The Best American Short Stories 2019, compiled by Anthony Doerr

This is my first year reading the Best American Short Stories, after having gotten more into short stories over the last few years. I am not a fan of multi-author anthologies, finding them impossible to “get into” when each new story is like starting a new book, and that’s particularly true here, where there is no unifying theme. From reading a number of both brief and in-depth reviews of this collection and its stories, I have the sense this year wasn’t the best for this series. Many readers only connected with a couple of the stories, though Doerr must have done something right in selecting them when readers’ favorites seem to vary so widely. Looking through the top reviews on this page shows that while most readers only really liked a third or fewer of the stories, almost every story made somebody’s shortlist, with little consistency in which were the favorites. For me the only two standouts are “Letter of Apology” by Maria Reva and “Omakase” by Weike Wang, but I liked these enough that I now plan to read the authors’ books.

So, a rundown in order of appearance:

“The Era” by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah: The collection begins with a dystopian tale about a world in which kindness and human connection are despised, and the resulting hole is filled with constant injections of drugs. All this I think is astute commentary on certain trends in our society, but I found other elements – like the genetic engineering that sometimes goes wrong and gives people only one personality trait – rather less relevant, and like many insecure sci-fi stories, this one spends way too much time talking about why their values aren’t our values and how our world became theirs. It’s as if we went around talking about the Renaissance all the time and why we aren’t like those people; I’m not buying.

“Natural Light” by Kathleen Alcott: This is perhaps the most literary and best-written story in the collection, about a woman in her 30s who discovers something new about her deceased mother. I admire the author’s skill a lot, but her subject matter was too run-of-the-mill to interest me in reading more, and I still can’t figure out the ending; the last couple of sentences just seem like word salad to me. The story made more sense once

“The Great Interruption” by Wendell Berry: An entertaining boyhood escapade turns into a local legend, which is then used to comment on the demise of local culture in America. A well-written story, though Berry’s nostalgia for the rural America of yore is steeped in white male privilege, which though not acknowledged becomes visible at one point when the females privileged to hear the original story are referred to as the “housewives and big girls” of the community (it contained no other adult women).

“No More Than a Bubble” by Jamel Brinkley: Two college boys crash a party with the goal of hooking up with a pair of slightly older women, and wind up way out of their depth. It’s a vividly told tale but I didn’t really know what to make of this one. The problematic aspects of the boys’ sexuality are clearly acknowledged, but I didn’t know how to reconcile Ben’s

“The Third Tower” by Deborah Eisenberg: In a vaguely-sketched dystopian world, the medical system tries to stamp out the creativity and possibly repressed memories of government-sponsored horror from the mind of a young woman. This one was a little too on-the-nose for me, and Therese’s gullibility and eager compliance made it harder for me to have strong feelings about what was being done to her.

“Hellion” by Julia Elliott: An adolescent girl in rural South Carolina befriends a visiting boy, and unfortunate consequences follow from their actions. It’s sweet enough I suppose, but what Doerr cites as its exuberance and courage, for me was just over-the-top in a way that seems almost careless: the character referred to as having grown up “before the Civil War” early enough in the story that we don’t yet realize this isn’t meant literally (it’s set in the 1980s or thereabouts); the young female narrator going off on a sudden tangent about people killing the planet when she’d never before mentioned an interest in science or ecology and again, it’s the 1980s. It all felt a bit haphazard to me, and the grounding in serious questions about whether this girl has a shot at a fulfilling life wasn’t quite enough to draw it back.

“Bronze” by Jeffrey Eugenides: A gender-nonconforming freshman meets an older gay man on the train home to college from New York, and has to finally decide whether he’s actually gay and if not, whether his self-expression is worth letting people read him that way. Interesting enough but didn’t do much for me, though I did find it interesting that Eugenides developed the older man, who without getting a point-of-view would have just been a standard creep.

“Protozoa” by Ella Martinsen Gorham: A 14-year-old girl tries to establish her self-identity in both the real and virtual worlds. Doerr perhaps sells this one short by calling it a cautionary tale about the amount of investment teens put into their online lives; in many ways Noa seems to live more in the real world than a lot of teens (she interacts with quite a few people in real life over the course of the story), and I found myself thinking that the cautionary message might have been sent more effectively. But I’m not sure the author actually intended the story as anything so simple: what might have been portrayed as traumatizing cyberbullying in another story, Noa seems perfectly well-equipped to handle and even in some ways to welcome, while her real story is about trying to establish herself as someone darker and edgier.

“Seeing Ershadi” by Nicole Krauss: A dancer and her friend both attribute newfound motivation to leave bad situations to visions of actor Homayoun Ershadi. This one didn’t really do anything for me. It seems to have a hole at its center: we hear a lot about the plot of the Iranian film Taste of Cherry, and a lot about the narrator’s friend’s life, while the narrator’s own life and decisions are sidelined. It is sweet though that according to the author’s note at the end, Ershadi read and was touched by the story at a difficult point in his own life.

“Pity and Shame” by Ursula Le Guin: An outcast young woman in a late 19th century California mining town cares for a lonely mine engineer injured in an accident, and the two of them and a doctor all form a bond. A sweet story but not one that leaves the reader with much to think about, despite the author’s legendary status.

“Anyone Can Do It” by Manual Muñoz: A young mother struggles to figure out how to pay the bills when her husband, along with other farmworkers, is suddenly snatched by immigration. Timely, certainly, though set in the 1980s rather than the present, and the author adds some complexity in that, for instance, Delfina doesn’t actually seem to like or miss her husband much. But she was a bit of a hollow character that was hard for me to root for, and

“The Plan” by Sigrid Nunez: Inside the mind of a killer. Interesting enough, but didn’t do much for me.

“Letter of Apology” by Maria Reva: In late Soviet Ukraine, a KGB agent is required to extract a letter of apology from a renowned poet for making a political joke. The agent, who narrates the story, is in denial about certain aspects of his own life, leading him to wildly misinterpret the behavior of the poet’s wife. I loved this one: there’s a ton of humor in the contrast between the dread image of the KGB and the reality of the bumbling and confused Mikhail, as well as the absurdities of the system as a whole. The whole story is full of dark humor and the changes wrought in both Mikhail and Milena seemed very real and sympathetic to me. I was excited to find that the author has also published this as part of a whole collection of linked short stories.

“Black Corfu” by Karen Russell: On a Croatian island in 1620, ruled at the time from Venice, a black man wanted to be a doctor but is permitted only to cut the hamstrings of the dead, meant to prevent them from rising again as less-violent zombies, known as vukodlak. He’s falsely accused of botching a procedure – or is the accusation really false? This was my first exposure to an author who’s gotten a lot of buzz lately, and the story hits a lot of buttons in terms of racial prejudice and glass ceilings, but didn’t actually work well for me.

“Audition” by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh: A young man who wants to be an actor instead, for unspecified reasons, works on construction sites owned by his father, a real estate developer, and seems to be falling under the spell of crack. This didn’t do much for me.

“Natural Disasters” by Alexis Schaitkin: A young New Yorker moves to Oklahoma with her husband, where she takes a job writing descriptions of houses for sale and tries to fit everything that happens into some meaningful narrative of her life. I enjoyed the narrator’s voice, her obvious pretention and her adult awareness of it when telling the story from the vantage point of many years later, but I was underwhelmed and unconvinced by the “big event.”

“Our Day of Grace” by Jim Shepard: An epistolary story about the American Civil War: two southern women write letters to two Confederate soldiers, one of whom writes back. The letters are credible enough but the Civil War has also been pretty well done to death as a setting, and in my view this didn’t do anything new or exciting.

“Wrong Object” by Mona Simpson: A therapist treats a man who at first seems boring, but then reveals that he only experiences sexual attraction to adolescent girls, though he insists he’s never acted upon it. This is interesting, but perhaps too short for me. I would have liked to know a little more about the therapist’s life, which is only vaguely hinted at, and to have seen the consequences at the end developed a little more. But the existence of people seeking treatment for pedophilia who have never acted on their urges was not new information to me, which may have blunted my reaction to the story.

“They Told Us Not To Say This” by Jenn Alandy Trahan: Blink and you’ll miss this 7-page story, told in the first person plural about a group of second-generation Filipina-American girls who are second-class in their families but find empowerment on the basketball court. This is the one story no reviewer seems to have highlighted as a favorite, and I can see why not.

“Omakase” by Weike Wang: A Chinese-American woman in her late 30s goes out for omakase (in Japanese, “I’ll leave it up to you”; in restaurants, sushi selected by the chef) with her white boyfriend, who increasingly shows his obliviousness about racial issues and his dismissive and condescending attitude toward her, despite the fact that she’s the one to do most of the sacrificing and pay most of the bills in their relationship. It’s interesting to see the widely varied responses that reviewers have had, some feeling that all the ways in which the woman is marginalized and put down in the world and within her own relationship to be too stereotypical, while others seem to take the boyfriend’s opinions at face value and view her as too sensitive and neurotic for her own good. Those varying responses are certainly a testament to the realism of the story. She is a bit neurotic, but to me much of this is the conflict generated by her instincts telling her she’s in a bad situation, while everyone around her (boyfriend, family, friends) insists that the only problem is her – thereby robbing her of the sense of self-worth she needs to actually stand up for herself. She comes across as real and vibrant, as do the racial issues addressed, and I’m interested in reading Wang’s novel.

Overall, an interesting collection of stories I don’t regret reading, but that took me a really long time to get through. I’m not sure if I’ll try another of these collections, but I did at least discover a couple of promising authors.

3

3

A Woman of No Importance by Sonia Purnell

This is an engaging book about a totally badass historical figure, though I’m left unconvinced that the author really had enough information to write a book about her.

Virginia Hall was an American woman who, during WWII, worked undercover in France for first the British and later the American intelligence agencies. She helped organize and arm the French Resistance, spied for the Allies, and later even directed guerilla activities herself. She faced incredible dangers to do so, and with about two years behind enemy lines, spent much more time in France than most operatives, despite the comrades regularly being hauled off by the Gestapo to be tortured and sent to death camps. She had plenty of adventures and near-misses, including once having to escape over the Pyrenees on foot in winter, an even more impressive feat given that she walked on a wooden leg after shooting herself in the foot years before.

Hall is certainly an impressive figure, and I am glad to have learned about her and enjoyed the book. After the first couple of chapters early on, relating the first 30-odd years of her life before sneaking into occupied France, the book is overwhelmingly focused on high-tension WWII exploits, and written in a fluid style that makes for quick reading. I’ve read my share of WWII books considering this is not my favorite subject, but I learned some new things here about the French Resistance, and the book introduces readers to numerous impressive men and women who risked and sometimes lost their lives fighting the Nazis.

That said, Hall herself – no surprise here – was secretive, and refused to share war stories even in later years with the niece to whom she was close, so I have some questions about where all the author’s information comes from. In particular, the author is quick to describe Hall’s thoughts and feelings about events without attributing them to any particular source, leaving me to suspect she made them up. Also, that same reticence on the part of the book’s subject left me confused about just how Hall was accomplishing the things she did. Somehow, Hall would arrive in a place where she knew no one, and despite Purnell’s repeated insistence that Hall was security-oriented and had no patience for loose-lipped operatives, within as little as two days she would have some new person apparently in on the secret, risking their life to accompany her on dangerous missions, while she risked hers in trusting them. Obviously Hall was an excellent judge of character since this virtually always worked out, but the book doesn’t give any sense of her methods, probably because the author doesn’t know.

I also came away with the sense that Purnell was perhaps a little too enamored of her subject, heavily criticizing anyone Hall didn’t get along with. It’s interesting that Hall’s career never really went anywhere except in occupied France: before the war she largely seems to have been held back in her attempted diplomatic career by gender prejudice, and it was at least partially the same story afterwards in her years with the CIA. However, I couldn’t entirely share the author’s indignation with the CIA’s failure to fully utilize Hall’s talents when during the decades after WWII the agency was busy toppling democratically-elected progressive leaders in Latin America to replace them with right-wingers who were friendly to American business interests and whose torture and murder of dissenters was pretty similar to the Nazis’ methods. While Hall’s having a desk job during those years doesn’t exempt her from her share of moral culpability – which Purnell never acknowledges – it at least lets the book focus instead on the straightforward excitement of the French Resistance years, with everything after that summed up in a single chapter at the end.

As an interesting and enjoyable book that introduced me to an impressive woman I would not otherwise have known about, I found this worth reading. But it’s sufficiently biased and speculative that I find it a bit difficult to recommend.

Bondage by Alessandro Stanziani

I picked this book up with the hope of learning about how serfdom actually worked in 18th century Russia and eastern Europe, and I did learn from it, though as with a lot of academic books it seems to have been written with the expectation that only about 12 people would ever read it, all of whom are other researchers in the same or related fields. The writing is unnecessarily dense and there are a lot of unexplained references to authors that this one is apparently refuting.

That said, the author’s thesis is an interesting one: essentially, that in the early modern era, Europe wasn’t so much divided between states where workers were free and states where they were serfs, as on a continuum. Workers in England and France weren’t nearly as “free” as you might believe, and labor laws were actually getting stricter at the time. Workers were often required to sign long labor contracts (a year was common, much longer was possible), and there were criminal penalties for leaving before a contract was completed, with the result that “runaway” workers could be jailed, fined, or even in some rare cases, whipped. Meanwhile, Russian serfs had more freedom of movement than some sources have given them credit for, with some going back and forth between town and the estates, and some areas of the country not sending back runaway serfs at all. Serfs could also initiate lawsuits against landowners, and some won their freedom this way (generally it seems because the landowners as non-nobles weren’t actually qualified to own populated estates), though as always the poor winning lawsuits against the rich was quite rare.

As someone unfamiliar with the literature the author is responding to, I found the arguments related to England and France (and the general descriptions of forced labor in Eurasia and in certain Indian Ocean colonies of the European powers) more coherent than the arguments about Russia. In some places it seemed like Stanziani was being overly technical, as when he points out that the laws establishing serfdom were all really about establishing who could own populated estates rather than delineating serfdom per se. I’m unclear on why this is important. He also seems to gloss over a lot of abuses described in other sources – granted, my other reading on this topic involves popular rather than academic sources, and this book is much too technical to engage with works of that sort at all. But while he states that Russian serfdom was nothing like American slavery, he doesn’t provide much basis for this conclusion.

At any rate, I’m clearly not the intended reader for this book, but I did get some interesting ideas from it. I’d love to see a book on this topic that’s a little more accessible for the general reader.

2

2

Chrysalis by Kim Todd

This is a lovely biography of an early female scientist, by an author who clearly put a lot of care and interest into learning about Maria Sibylla Merian and her work. Born in Germany in the mid-17th century, Merian trained as an artist but was fascinated by the metamorphosis of insects from childhood. She continued to study them throughout her life, observing and creating gorgeous paintings of their life stages, and ultimately traveled from Amsterdam to Suriname in 1699 to study insects there, in one of the earliest European scientific voyages. She was a pioneer of ecology: studying life in its natural context rather than collecting dead specimens to observe under a microscope.

A challenge the author faces is that little material about Merian’s personal life survived, though she left lots of notes and artwork. So there is some speculation here, though Todd often suggests multiple possibilities where we don’t know the answer rather than pushing for a particular interpretation. What we do know about Merian’s life is so tantalizing that I wish we had more: what really happened in her marriage, which resulted in a divorce at a time when this was highly unusual? What led her to join, and then leave, the severe, cult-like Labadist sect, and what was life like in it? There’s a lot we don’t know, but Todd fills in many of the blanks with history, by researching life in Germany, the Netherlands and Suriname at the time Merian lived in these places. I’m surprised others have found the book dry; to me it had a quiet warmth that really drew me in.

Unusually for a biography, this book continues well after Merian’s death, which occurs on page 225 out of 282. It then follows her daughters, her scientific legacy, and recent developments in ecology and studies of metamorphosis, all of which adds a lot to the book. I’d love to see more biographies engage with the context of their subjects in this way. There are also black-and-white illustrations as well as some color plates, many showing Merian’s work, though for me reading this alongside the illustrated children’s book Maria Sibylla Merian: Artist, Scientist, Adventurer was great because that one provides such a wealth of color paintings by Merian.

In the end, I enjoyed this a lot: it’s intelligent, accessible, and wide-ranging in its subject matter while telling what we know of the story of a remarkable woman. I love that Todd wrote this book at all: it’s surprisingly hard to find historical biographies (at least in English) of people who spoke languages other than English, and if they’re women without adventurous sex lives, forget it! But from these biographies Merian emerges as a fascinating person who deserves to be remembered.

10

10

Old Man River by Paul Schneider

This is a quirky mix of historical anecdotes with a bit of the author’s personal travels, endearing if not particularly cohesive. The geographical scope is quite broad, encompassing areas of the Mississippi River basin quite removed from the river itself (40% of the U.S. is in the Mississippi basin, though the points Schneider writes about are either along the river or east of it). Early sections cover the river basin’s geological history, and then move into Native American history mostly via archaeology, and the section on colonial explorations and warfare is extensive; we’re more than halfway through the book before the United States as a country is born. Because the book is not long and the time period covered is, the author seems to just tell us the stories that suit his fancy, which produce an interesting mix. The portions dealing with Native American history have been done better in, for instance, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, though on the other hand I think this is the most in-depth treatment of the French colonial/exploratory presence in the future U.S. that I’ve ever seen, which speaks to their treatment in most histories as no more than nebulous antagonists off in the woods somewhere.

My favorite part was the 60-page “Life on the Mississippi” segment set between the Revolution and Civil War, covering boat travel up and down the river both before and after the introduction of steamboats, and also river pirates and the like. The Civil War section seems disproportionately long at around 40 pages, and was less interesting to me, and then the book wraps up with a couple of chapters on the extensive dams and other artificial changes made to the river since and their environmental impacts. Long story short, alterations to make the river easier to navigate and reduce yearly flooding also reduce the sediment settling at the mouth of the river to the point that Louisiana is losing a huge amount of land area every year, while major floods are even more frequent and destructive.

There are interspersed chapters about the author’s various travels on and around the river, which are not particularly eventful but are clearly meaningful to him, and add some emotional dimension to the book. Also, on one trip he takes his teenaged son and they run along the top of a train stopped by the side of the river, which makes him a super cool dad.

Overall, this book is kind of scattershot – the author is pretty clearly just relating whatever historical anecdotes are most interesting to him, without making any attempts at being comprehensive, and it would be easy to nitpick what’s included and what’s not. However, it’s pretty well-written and as light supplemental history and travel reading it’s perfectly fine.

3

3

The Anarchy by William Dalrymple

This is a very informative history of how the British East India Company colonized India. It begins with the formation of the company in 1599, but the crucial time period on which most of the book is spent is from about 1750 to 1803, when the British took advantage of the implosion of the Mughal Empire to take over first Bengal, then other Mughal territories, and finally other Indian kingdoms entirely, through a combination of war, financial maneuvers and diplomacy. In some ways the fact that it was a private company rather than a government doing all this feels almost incidental, as the East India Company was more or less a government (hiring its own armies, coining its own money, collecting taxes, etc.), with the exception that milking as much out of its subjects as possible was actually its overt goal, with all that wealth being taken back to England.

This isn’t a time period about which much has been written, considering the massive ramifications and the fact that English-speakers’ involvement would lead one to expect these events to be well-known in the English-speaking world. Dalrymple covers the many maneuverings, battles, atrocities, and personalities involved in detail. It’s very much a political/military/diplomatic history, giving little sense of what daily life in India was like, particularly for Indians, but even with a fairly narrow focus it’s a chunky read. Dalrymple draws from a wide variety of sources, including sources in Persian, Urdu, Bengali and Tamil, which makes the book feel much more complete than most stories of colonial takeover – although I think he might use slightly more, or more varied, sources in English, at no point did the book leave me in doubt about the goals, feelings or activities of the Indian rulers and their generals. There’s probably around as much information on Indian affairs as British ones.

All that said, I didn’t love this book. Perhaps because so many important figures drop in and out (between deaths and, for the British, retiring or being recalled to England, most leaders don’t seem to last more than about 10 years), and because there’s so much political and military ground to cover, the book is a bit dry even though Dalrymple is clearly doing his best to make an engaging narrative of it, and doesn’t ever get too bogged down in mundane detail. There’s a lot of atrocity: famines, war, and a great deal of torture. And perhaps most relevantly regarding the book’s quality, Dalrymple seems to take somewhat black-and-white views of the personalities involved. Most of them come across as villainous, which almost always seems justified by their activities, but I couldn’t quite get behind his admiration for Warren Hastings, or distaste for Philip Francis on the apparently sole basis of his enmity toward Hastings. No matter how admirable Hastings might have been in his personal life, or how much true attachment he felt toward India, he nevertheless presided over a part of its destruction.

In the end, this is a valuable book, very informative, professionally put together and well-sourced, with an extensive bibliography, useful glossary and many color plates showing relevant Indian and European artwork. All around, an admirable work. Nonetheless, I breathed a sigh of relief to be done with it.

3

3

The Newcomers by Helen Thorpe

Helen Thorpe is an excellent writer of journalistic nonfiction, and always picks great topics for books, which is why I’ve read all of them. Unfortunately, the quality of her books seems to me inversely proportional to how much she features herself in them, and The Newcomers falls on the wrong end of that scale. But this book has an even more basic problem, in which Thorpe appears to have committed herself early to a particular premise and clung to it even as it proved increasingly infeasible and even inappropriate.

The premise is that Thorpe spent a year embedded in a Colorado high school classroom in which non-English-speaking students newly arrived in the U.S. learn the fundamentals of the language. Most of these students are refugees, hailing from various war-torn parts of the globe, from the Middle East to Africa, Southeast Asia to Central America. Teacher Eddie Williams generously agreed to host her, and Thorpe shows up eagerly to class, hoping to write about the lives of these kids and the circumstances that led them to flee their homelands.

And here’s where the problems start. First, Thorpe was determined to write a book about a group of people, who, by definition, don’t speak her language, and she doesn’t speak theirs. Second, those people are traumatized, confused teenagers, with traumatized or missing parents who understand life in the U.S. no better than their children do. Gradually the book turns into Thorpe pumping for information on the personal lives of people who don’t actually want to share. Even the teacher, her entry point, doesn’t want to go there, which doesn’t stop her from highlighting more than once that he refused to talk about the circumstances of his having a child outside wedlock. (Good grief, it’s the 21st century. This is probably the least interesting thing about him.)

Okay, she can do without the teacher’s inner life. But the students are no more forthcoming, and no wonder. Throughout the book, numerous older students and interpreters, former refugees themselves, advise Thorpe against prying into the kids’ lives: they’re new, they’re traumatized, they’re not ready to discuss their worst experiences with anyone – let alone, one presumes, the general public. But instead of changing the plan and focusing the book on people who were ready, she substitutes by speculating about the kids’ inner lives, or by recounting mundane classroom activities as if they were freighted with deeper meaning than seems evident to me. She notes that when Jakleen, an Iraqi girl who is one of the book’s more prominent characters, started and then stopped wearing a hijab, “I was not sure how to interpret this statement, and she never cared to enlighten me”; when Jakleen stops talking to a boy, it’s “for reasons that remained unclear.” When Methusella, a Congolese boy also prominently featured, makes a collage in group therapy, it’s “one of the few times [he] had revealed himself all year.”

He only actually revealed himself to the school therapist, but she hastened to pass on details of his work’s symbolism to the author, in one of many moments that made me question this story both in terms of consent and storytelling. All but one of the kids agreed to “participate” in her project (perhaps feeling it would have been rude or pointless to refuse, when she was in their classroom every day regardless), but none of them ever tell their stories fully, the way the subjects of Thorpe’s previous books did, leaving their experiences rather opaque. Which means the book loses out on including any more depth than what Thorpe was able to glean by following the teenagers around for awhile, and that most likely all this speculation about their emotions and histories was published without their first having the opportunity to withdraw consent. I’m sure many worthwhile nonfiction books have made their subjects uncomfortable, but it’s one thing to do that to an informed adult, another to an underage refugee with limited English proficiency.

And then there’s just so much of Thorpe in this book. She seems determined to convince readers how important her friendship is to these kids, and to the two families – Jakleen’s and Methusella’s – to whom she becomes a regular visitor. Unfortunately in her interactions with the teens she comes across as stiff and hopelessly middle-aged, and the focus on her own reactions takes away from informing the reader. For instance, when Methusella’s father endeavors to explain the situation in the DRC to her, she writes, “Then we got into an alphabet soup of armed groups . . . I got lost somewhere in the middle, amid the acronyms and all the tribal stuff. I could not absorb all the details, but I came away with the notion of a jumble of allegiances and betrayals, mixed with a lot of weaponry.” Look, lady, I don’t care about your experience of learning about Congolese history. This is supposed to be a book about the refugees, not your memoir.

All that said, this book did engage me. It’s accessible and, especially as we get to know the families, the kids and their parents are very easy to empathize with. I enjoyed spending time with them and wanted the best for all of them. While there’s a ton of fiction and memoirs out there about refugee experiences, there’s much less popular nonfiction, so it’s a great idea for a book. And I learned a bit about the refugee resettlement process from it. The contrast between the Congolese family, which quickly seems to thrive in the U.S., and the Iraqi girls and their widowed mother, all of whom struggle quite a bit, is interesting and vivid. Thorpe’s brief trip to the DRC and meetings with Methusella’s friends and relatives there was a nice touch. But I suspect Thorpe would have produced a far better book if she’d regrouped and written about people willing and able to fully engage in the process, and kept herself out of it.

3

3

Aristocrats by Stella Tillyard

This is a well-researched and engagingly written group biography of four sisters, daughters of a duke and great-granddaughters of King Charles II of England and one of his mistresses. Caroline, Emily, Louisa and Sarah Lennox all wrote to each other (and third parties) constantly, leaving a trove of correspondence that the author used as material for this book. Tillyard brings the four of them – and the people and places around them – to life with vivid descriptions, and seems to have a strong handle on the personalities and psychologies of each of the sisters. She also includes a lot of background information on their world where it enhances the story: from everyday details about the dozens of departments involved in the running of an aristocratic household, to background on the Irish Rebellion of 1798, in which Emily’s son Edward Fitzgerald was a leader.

It is a well-told story and makes for much quicker reading that Tillyard’s A Royal Affair, splitting its attention between human feelings and relationships on the one hand, and history on the other. While none of the sisters seem to have contributed much to history in their own right or really stepped out of the roles of wives/mothers/lovers, they did have pretty interesting love lives: one eloped and was temporarily estranged from the family; one began an affair with her children’s tutor and later married him across class lines after her first husband’s death; one was George III’s crush, before hastily getting into an unhappy marriage followed by a public divorce. In her preface, Tillyard emphasizes the intimacy of the sisters’ letters, allowing modern readers to connect with them even across a great gap in time, and this is certainly true.

The subtitle is a little misleading as to the time period, though. About 80% of the book focuses on the period from the 1740s through 1770s; in my edition, it’s not until page 397 out of 426 that we hit the 19th century. A couple of other better publishing decisions might have been made, in that the chapters are way too long and might have been broken up for easier reading, and there’s no family tree, which becomes especially confusing when talking about Emily’s life with her 22 children. Even a list of everyone’s kids with birth and death dates would have been extremely helpful.

I’m also never happy to see a nonfiction author who doesn’t cite the sources of specific facts. I understand that this is original research and the author does list her sources generally in the back, including mostly archival sources. Still.

In the end, I enjoyed reading this book and found it quite interesting, but never found myself with much to say about it. Maybe it’s because it’s largely a domestic history, not too different from stories that could be told about many other families; its four subjects were ultra-wealthy and privileged, but in the end we are reading their story rather than someone else’s simply because they happened to leave more writings behind. Maybe it’s because Tillyard did such a good job bringing her subjects’ personalities to life that, while I enjoyed reading about the sisters’ complex personalities and admired each of them at various points, I ultimately didn’t like them very much; they all come across as rather self-satisfied and entitled in the end. So I didn’t love the book, but I did like it, and it has a lot to recommend it whether your interest is anthropological or escapist.

Daily Life in 18th Century England by Kirstin Olsen

This is a textbook, but it's a very readable one and quite interesting if you are curious about the subject, without the academic pretension or dryness that can drag works down. Chapters cover subjects such as food and drink, clothing, entertainment, politics, religion, education, race and class, family relationships, the economy, the state of science, and more. The second edition reorganizes the chapters and expands a few of them, as well as including more primary documents, but the short, clearly labeled chapters of the first edition are handy if you want to skip around and read it in bite-sized chunks.

A couple of fun facts: clocks with minute hands were a new thing in the 18th century (previously they only had hour hands), and non-poor people were mortally offended by poor people keeping dogs.

I wish I could find such cogent, detailed and accessible studies of other parts of the world during this time period, but if you're interested in England, Olsen has you covered.

I collected books on my home shelves that I would actually like to read. And which I haven’t yet read, or did so when too young to remember them well now. This is probably a year’s worth of reading right here.

5

5

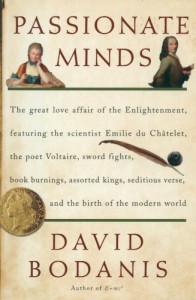

Passionate Minds by David Bodanis

This is a frothy historical biography best described by its title. Unfortunately it does not live up to either the dramatic promise of its subtitle, or to the serious intentions stated in its preface. In that preface, the author bemoans the lack of recognition of early 18th century aristocratic French scientist Emilie du Chatelet, stating that she was written out of the canon by men who didn’t believe a woman could make serious contributions, and that the society hostesses and later feminist writers who might have championed her lacked the technical knowledge to understand her work, with the result that female biographers just focused on her wild sex life. Bodanis then proceeds to tell a story of du Chatelet’s life focused on her wild sex life, with only brief segments about science that provided little enlightenment to this reader.

In particular, Bodanis is enamored of du Chatelet’s tumultuous 15-year affair with Voltaire, and structures the book around that. It’s almost a dual biography (to the point that my library shelves it as a biography of Voltaire), except that Voltaire outlived du Chatelet by decades and those years aren’t covered in this book. Bodanis seems attached to the notion that this relationship provided du Chatelet with the confidence and support she needed to engage in scientific work, but it seemed to me that much of the evidence he provides argues against this conclusion. For instance, in one episode, Voltaire decides to enter a scientific competition, and du Chatelet spends her days assisting him with his experiments, but for some reason feels she can’t tell him where he’s going wrong, and meanwhile secretly stays up late every night working on her own submission, which she hides from him and ultimately mails off with the assistance of her extremely laid-back husband, who appears genuinely indifferent throughout to the fact that she’s living openly with another man. Which of these people is actually providing useful support, and which one has become an obstacle? I came away from the book with the impression that du Chatelet’s penchant for falling wildly in love with various men was a tragic distraction from her work, perhaps in part due to the author’s focus.

It’s a focus, in the end, that involves compressing complicated events into such short segments that I found them a bit difficult to keep track of, while lovingly expanding on descriptions of emotions and relationship dilemmas. These people wrote constantly, so I don’t think Bodanis is speculating, but it does come across as frothy. Interestingly, in the acknowledgements he says that while writing the book, he sent it out in installments to friends, and they and their friends and coworkers all eagerly signed up for more. But then, he says, that draft, nearly twice the length of the book he ultimately published, “wasn’t quite right. . . . There was to much to-ing and fro-ing, too much textual analysis and historical background, and too much elaboration of science and the biographer’s evidence.” I for one suspect I would have thought more of this book if it had included all that stuff, and the contrast between the word-of-mouth excitement Bodanis describes around his draft and the small number of readers who have rated the completed version on Goodreads makes me suspect it’s not just me, and what he cut was more essential than he realized.

Ultimately, this was an interesting book that I don’t regret reading, and it had a great start, but after 60 pages or so I began to fall out of love with it and never regained that level of enjoyment. Great material, but perhaps not the best possible treatment of it.